|

As the international community persists in its silence, the patriarchal regime keeps burying its daggers of discrimination and violence in the flesh of our societies. Just months away from the murder of teenage Armita Geravand, on behalf of the Iranian morality police; just days away from the murder of Giulia Cecchettin, 105thcase of femicide in Italy in 2023; just minutes away from the denial of safe pregnancies to all those women in Palestine, questions around female liberation and solidarity become vital: femininity, despite geographical distances, is caught in the tight grasp of patriarchal clutches. For our mothers, daughters, sisters, we must unveil violence and learn that love, stripped of rancour, is our only way out of this plagued circle. Amrita Geravand, 16 years old, was seriously injured on 1st October when travelling on a metro in Teheran with two friends, and no headscarf. Here she was approached by some female morality police officers, she was seen falling and being dragged off the platform by CCTV cameras in the station. The morality police was accused of attacking her by various sources due to not wearing a hijab, and the Tehran government released a suspicious information campaign on the matter. Amnesty International analysed the footage shared by Iranian authorities and found there was no altercation, the material had been edited, the frame increased and over three minutes had been removed from the video. After a 28 day long coma due to brain damage, Amrita passed away in the intensive care unit of an army hospital.

These events occurred after Iran had approved a “hijab bill” in September 2023, a new legislation mandating harsher penalties for women who didn’t follow regime rules. Previously, Article 368 of the Islamic penal code was taken to be the hijab law stating that women breaching the dress code faced between 10 days to 2 months in prison, or a fine between 50,000 to 500,000 rials (approximately £1 to £10). The new bill, on the other hand, states that anyone wearing the hijab “wrongfully” faced 5 to 10 years in prison, and a higher fine of up to 360 million rials (equal to £6,850), with millions living below the poverty threshold. As well as this, the bill proposes fines equal to three months of profits for business owners not enforcing hijab requirements in the workplace, punishments to celebrities, exacerbated gender segregation in universities and public spaces, and the use of AI systems to enhance surveillance of breachers. The use of new technologies, such as AI, to promote the surveillance and incrimination of women is a phenomenon that should concern us all on a global scale, with the opportunity of this being used to track people’s reproductive choices, or exacerbate gender gaps in the workplace for instance. What would happen if an anti-abortionist government was able to access private information to use in a court case? Or if a similarly authoritative government suddenly rose to power and had access to information about all women not adhering to its sexist legislations? The question of emerging and established technologies, particularly those dealing with confidential information, must always be scrutinised through the lens of female and reproductive justice, to understand who would be most vulnerable or targeted by these mechanisms. The dreams of female liberation are still distant in the collective conscience, particularly when injustices and violent patriarchal regimes are upheld beneath the eyes of all in the international community. Older technologies, too, must be revised under the scrutiny of the female gaze, considering the recent investigation due to the fact the Danish government was sued by 67 Inuit women for a sterilisation campaign conducted in Greenland, against their knowledge, in the 1960s and 70s. By inserting intrauterine devices in these women’s bodies without their consent, to limit birth rates amongst indigenous populations, the government caused serious health issues and infections, while thieving them of their fertility. With women themselves, turning against this liberating goal, this endeavour encounters even more obstacles. An example of this, is the Italian premier Giorgia Meloni who was compliant, amongst many other women, with her partner’s notorious comment on national tv about the usefulness of reading Red Riding Hood when talking about a group rape on a young girl. He claimed that “if you avoid getting drunk or losing your senses, you also avoid finding problems, otherwise you'll find the wolf”. In other words, the issue is not the wolf and its predatory behaviours, but rather the fact that you may be vulnerable to it, that you are in a position to be attacked and therefore you are responsible for the consequences. This is the logic that governs and enables the practices, narratives, gestures that degrade and endanger women, at the hands of their male counterparts. Over the last week, the body of a 22 year old woman, Giulia Cecchettin, was found along the Bàrcis lake near Pordenone. She was seen meeting with her ex-boyfriend, who attacked and dragged her into his car before driving away towards Germany. She is the 105th woman who was murdered in Italy in 2023, so far. The numbers are horrifying: femicide is an epidemic in its own right, which is often maintained by the shared notion that it is normal for “love” to kill you, if this becomes too jealous or controlling. This is not acceptable: for love to be true, it must ascribe all rancour and resentment. It must embrace freedom. The common narrative, when cases of femicide arise in Italy (once every 72 hours, precisely), is that he was a “good father”, a “golden boy”, an “exemplary young man”; and this is precisely the problem. It is ordinary men, not monstrous sociopathic beasts, who are engaging in such behaviours: for this reason, it is fundamental that men must interrogate themselves first, put their actions and their identities in question, to find the unhealthy seeds of patriarchal thinking before they take root. Similarly, women must be able to find those same seeds, that in this case justify, accept, reinforce and often reproduce the negative effects of violent and controlling masculinity in men, and in themselves. This is why, if you’re a woman, you’re not free until the tentacles of patriarchal thinking have been leashed both globally and locally. You could have been a 16 year old in Tehran. You could have been an indigenous woman in the 1960s. You could have been the unfortunate girl abused by a gang on a night out in Sicily. Similarly, if you are a man, you could’ve been born a woman. You could have been the prey, not the wolf. The work that must be done is to unpluck the splinters of domination and patriarchal thinking that too often get stuck in our sense of place and entitlement. This requires care and boldness, strength and gentleness, to be able to find common ground and abandon all resentment, both as violators and victims. It must not be hatred to move us, but justice, and justice alone. In the words of aboriginal activist Lilla Watson, “if you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” This is the difference between charity and solidarity: one is bound to contextual meaning, whereas the latter is intertwined with the ideal goal of collective liberation, emancipation, participation. But more fundamentally, this is not a question of contexts or luck: we are required to stand for the liberation of all women, because the liberation of some, and not others defies the notion of “freedom” altogether. We are free only if all women, in all places, are free. In the same way we are all free only once the people of Palestine, or Darfur, or Tigray, are free. Liberation is collective, otherwise it is a play of power wherein we find ourselves in a position of privilege. And nobody is justified in being the wolf preparing to prey on the red veils of injustice all around us.

0 Comments

🇮🇹 E tu osi chiamarmi terrorista Mentre guardi la tua pistola Quando penso a tutte le azioni che hai compiuto Hai saccheggiato molte nazioni Diviso molte terre Hai terrorizzato la loro gente Hai governato con mano di ferro E tu hai portato questo regno di terrore nella mia terra - Joe McDonnell, da "Un senso di libertà" (1983) Dall’alba di sabato, i recenti attacchi di Hamas hanno preso di mira Israele e hanno coinvolto il resto del mondo. Vari media stanno tentando di dare un senso a questi eventi in corso, rivelando come le informazioni dei vari narratori siano profondamente intrise di ideologie e opinioni contrastanti. Il tentativo di essere “neutrali” non è plausibile in qualsiasi resoconto, ma diventa impossibile quando l’obiettivo è spiegare il rapporto tra Israele e Palestina. Cosa viene denunciato, cosa viene ignorato, chi è il ''terrorista'', chi è la ''vittima'', chi è il ''noi'': tutte queste scelte implicitamente lasciano trapelare la verità del proprio giudizio nel linguaggio. Per questo motivo, crediamo che questo sia il momento in cui l’informazione e il giornalismo debbano abbracciare il vero potere politico della penna. È tempo di riconoscere come l’informazione può portare alla guerra o guidarci verso la pace. Israele: una breve storia e mitologia

Secondo lo storico israeliano Ilan Pappé, il caso israelo-palestinese mostra chiaramente come la disinformazione storica e la manipolazione dell’informazione possano consentire l’oppressione di una popolazione e legittimare un regime di violenza e oppressione. I principali media europei hanno spesso preso come oggettive le narrazioni portate avanti da Israele, violando così il diritto morale del popolo palestinese alla propria terra. Nel suo libro “Dieci miti su Israele” (2017), Pappé mira a dissipare queste narrazioni attraverso la documentazione storica. (1) Qui viene presentato un breve riassunto di alcuni, con un glossario incorporato, prima di tentare di dare un senso agli eventi recenti e alla loro rappresentazione. 1. Intorno al 1800, prima dell'avvento del sionismo, la Palestina non era una terra deserta: vi abitava una fiorente società araba, per lo più islamica e rurale, come in altre zone limitrofe. Nel 1916, le potenze coloniali di Gran Bretagna e Francia si unirono nell'accordo segreto Skyes-Picot e divisero l'area creando stati-nazione (o wataniyya, in arabo) e la Palestina cominciò a considerarsi un paese arabo indipendente. Qui, sotto il dominio britannico, venne definita un'unica entità territoriale unendo le tre province del sud di Beirut, Nablus e Gerusalemme per le loro somiglianze linguistiche, culturali e tradizionali. Mentre aspettava l'approvazione ufficiale dello status internazionale nel 1923, il governo britannico rinegoziò i confini dell'area. Lo spazio geografico della Palestina era chiaro, ma non a chi appartenesse tra i nativi palestinesi o i nuovi coloni ebrei. 2. Il sionismo è un movimento che crede nello sviluppo di un progetto ebraico nazionalista, ora incarnato da Israele, sulla premessa che questo fosse “una terra senza popolo per un popolo senza terra”. Questo fu istituito nel 1897 sotto l'austro-ungarico Theodor Herzl, e successivamente guidato dal primo presidente di Israele, il russo Chaim Weizmann. Questa ideologia era condivisa solo da una minoranza di ebrei ed il movimento faceva molto affidamento sui funzionari britannici e, successivamente, sul potere militare israeliano che era fortemente intrecciato con quello degli Stati Uniti. 3. Sionismo ed ebraismo NON sono la stessa cosa: la falsa fusione dei due può essere ricondotta all’emulazione della nazionalizzazione in atto in Europa e (da qui) oltre, nonché alla necessità di fuggire da una società che discriminava gli ebrei. Nella visione sionista, la storia della Palestina è limitata a fasi in cui questa è stata dominata da altre culture: dalla Palestina dei miti biblici, alla Palestina governata dai romani, dai crociati e, infine, dai sionisti. 4. Quando nel 1882 arrivarono i primi coloni sionisti, questi cominciarono a considerare i nativi come stranieri e invasori. Si trattava di un movimento colonizzatore simile a quello che stava avvenendo per conto delle forze europee nelle Americhe, in Sud Africa, in Australia e in Nuova Zelanda. Dalla fine del XIX secolo sorsero conflitti tra la comunità palestinese e i coloni sionisti, e la prima creò una Conferenza nazionale palestinese nel 1919 con lo scopo di comunicare con il governo britannico e i leader sionisti. Nel 1928 gli inglesi proposero un patto di uguaglianza tra i due partiti: i palestinesi, contro la volontà della maggioranza, accettarono; i sionisti rifiutarono. Seguirono conflitti violenti, esacerbati dal fatto che furono sottratte terre che appartenevano ai palestinesi da secoli. Fu qui che il predicatore siriano, l'esiliato Izz al-Din al-Qassam, riunì i suoi primi seguaci per intraprendere una guerra santa islamica contro gli inglesi e i sionisti all'inizio degli anni '30. Il suo nome fu successivamente adottato dall'ala militare del movimento Hamas. Nel 1947, l’ONU discusse per 7 mesi il destino della Palestina, dovendo scegliere tra due opzioni: un unico stato che includesse coloni ebrei ma che non consentisse un’ulteriore colonizzazione sionista (come proposto dai palestinesi), o una divisione della terra in uno stato musulmano e uno stato ebraico. Optò per quest'ultima. Il progetto sionista può quindi essere compreso come un progetto coloniale che è stato, ed è tuttora, accolto dal movimento nazionale palestinese come un fenomeno di resistenza anticoloniale. 5. La guerra del 1967 NON fu necessaria: Israele la vide come un’opportunità per confinare i palestinesi in Cisgiordania e Gaza come abitanti senza cittadinanza e prigionieri, consentita a livello internazionale come soluzione temporanea finché dall’altra parte non fossero emerse offerte di pace. In altre parole, se i palestinesi avessero accettato gli espropri delle terre, le severe restrizioni di movimento e la dura burocrazia dell’occupazione, allora gli sarebbe stato permesso loro di lavorare in Israele o trovare una sorta di autonomia; in caso contrario, si sarebbero scontrati con la forza dell’esercito israeliano. Ma ciò è solo storia: il pesante coinvolgimento di Europa e Stati Uniti nel caso israelo-palestinese, così come la complicità delle organizzazioni internazionali e il loro mancato riconoscimento della natura della violenza israeliana, persistono ancora oggi. Le narrazioni hanno il potere di creare il nostro mondo e per questo motivo comportano delle responsabilità. Cosa è successo la scorsa settimana Gaza è sotto il blocco militare israeliano illegale dal 2007. Sabato mattina, 7 ottobre, il gruppo militante Hamas ha attaccato varie aree israeliane circostanti la Striscia di Gaza, provocando uno degli attacchi più gravi che Israele abbia subito da decenni. Hamas è un gruppo militare fondamentalista islamico, che nel tempo ha guadagnato il sostegno popolare grazie alla fornitura di istruzione, medicine e assistenza alle persone che soffrivano a causa dell'occupazione israeliana nella Striscia di Gaza. Questo attacco ha causato almeno 200 morti, tenendo in ostaggio numerosi civili e soldati israeliani all'interno della Striscia di Gaza. La risposta israeliana essere riassunta nell’annuncio di un assedio completo su Gaza da parte di Yoav Gallant, ministro della difesa israeliano: “Ho ordinato un assedio completo su Gaza. Niente elettricità. Niente cibo. Niente carburante. Niente acqua. Tutto è chiuso. Stiamo combattendo degli animali umani e agiamo di conseguenza”. Ancora un’altra narrazione che convalida lo storico progetto coloniale e militare di Israele e la sua continua oppressione dei popoli nativi sul territorio. La violenza che Hamas ha perpetrato contro lo Stato israeliano non è giustificata, ma piuttosto spiegata attraverso questa breve presentazione delle sue origini storiche e contestuali. Insieme a questo, però, DEVE essere spiegata la violenza che Israele ha perpetrato contro i palestinesi nell’ultimo secolo. Un’omissione di tutto ciò è propaganda. Anche l'invocazione del violento attacco di Hamas in nome della “giustizia” è propaganda. Ma il riconoscimento che Hamas è un gruppo fondamentalista e militarista, nonché un sintomo della resistenza alla violenza israeliana che si estende nella storia, può offrire un modo più completo di inquadrare il problema e, si spera, far luce sulle sue soluzioni. Cos'è il terrorismo? Secondo uno studio condotto dal notiziario francese Le Grand Continent, l'attacco di Hamas divide il mondo in tre gruppi: da un lato paesi come Europa, India e Kenya, che condannano l'attacco di Hamas e sostengono Israele; una piccola minoranza che difende Hamas; e una grande maggioranza di paesi che si dichiarano “neutrali” e sostengono una cauta riduzione delle tensioni. Nel 1986, il giovane senatore Joe Biden affermò che “se non ci fosse un Israele, gli Stati Uniti avrebbero dovuto inventarsi un Israele per proteggere i propri interessi nella regione”. Questo non era solo un progetto politico, ma “il miglior investimento da 3 miliardi di dollari che facciamo”. Qui sorge la domanda su cosa simboleggi davvero Israele. Senza guardare troppo indietro nel tempo, il presidente francese Emmanuel Macron ha scritto: "Condanno fermamente gli attuali attacchi terroristici contro Israele", mentre il britannico Rishi Sunak esprime il suo shock per gli "attacchi dei terroristi di Hamas contro i cittadini israeliani" sulla base del fatto che “Israele ha il diritto assoluto di difendersi”. Se per “terrorista” si intende qualcuno che sostiene la repressione e la violenza, diffondendo allo stesso tempo il terrore per raggiungere i propri obiettivi, allora cosa rende il governo israeliano meno colpevole di Hamas? La risposta risiede nelle narrazioni, nella propaganda, nella violenza, nel silenzio, nella manipolazione e nella disinformazione. La Resistenza e le sue vittime Stare dalla parte della resistenza palestinese non significa legittimare la sofferenza delle vittime israeliane della violenza che molto spesso sono civili, giovani e anziani; significa piuttosto riconoscere i giochi di potere storici e ideologici necessari per affrontare il problema più profondo che è l’occupazione, l’imperialismo e il militarismo. La resistenza, soprattutto quando essa impiega mezzi violenti per sopravvivere, è spesso messa a repentaglio da contraddizioni etiche: la sofferenza di un popolo contro un altro, per esempio. Tuttavia, in un’occupazione militare, i giochi di potere non possono cambiare senza una qualche forma di ciò. Essere violenti contro un sistema che ti opprime e ti violenta è resistenza, non terrorismo. Nelle parole dello scrittore, attivista e internazionalista marxista palestinese Ghassan Kanafani, “l’imperialismo ha posto il suo corpo sul mondo, la testa nell’Asia orientale, il cuore nel Medio Oriente, le sue arterie raggiungono l’Africa e l’America Latina. Ovunque lo colpisci, lo danneggi e contribuisci alla rivoluzione mondiale.’’ La differenza tra terrorismo e resistenza è chi racconta la storia, o meglio chi possiede i mezzi più potenti per dare vita a tale narrazione. La causa palestinese quindi non è solo una causa localizzata in cui ci si aspetta che il popolo palestinese rimanga solo, ma un’opportunità per tutti coloro che nella comunità internazionale desiderano lottare contro l’oppressione e lo sfruttamento di solidarizzare con la lotta di queste persone. Solo in questo modo la storia potrà redimersi dall’ingiustizia ed educare un futuro in cui “gli oppressi vivranno, dopo essere stati liberati con la violenza rivoluzionaria, dalla contraddizione che li incatenava”. Il terrorismo è un sintomo del potere. Più precisamente, di chi ha il potere di diffondere tali narrazioni di terrore. Per combatterle, dobbiamo istruirci e trovare le cause profonde che stanno alla base dell’imperialismo e del militarismo, nonché della disinformazione e della propaganda. NOTE Per un ulteriore approfondimento, l'ebook di “Dieci miti su Israele” è reso disponibile gratuitamente in traduzione italiana dalla casa editrice Tamu Edizioni al seguente link: https://tamuedizioni.com/tproduct/467310025-775315736231-dieci-miti-su -israeliano And you dare to call me a terrorist While you look down your gun When I think of all the deeds that you have done You have plundered many nations Divided many lands You have terrorized their people You ruled with an iron hand And you brought this reign of terror to my land - Joe McDonnell, from ‘A Sense of Freedom’ (1983) Since the dawn of Saturday, recent attacks by Hamas have targeted Israel and engaged the rest of the world. Various media outlets are attempting to make sense of these ongoing events, whilst revealing how the information of various narrators is profoundly drenched in contrasting ideologies and opinions. The attempt to be ‘’neutral’’ is implausible in any recount, but this becomes impossible when the goal is explaining the relationship between Israel and Palestine. What is reported, what is ignored, who is the ‘’terrorist’’, who is the ‘’victim’’, who is the ‘’we’’: all of these implicit choices let the truth of one’s judgment seep through the cracks of language. For this reason, we believe this is a time for information, and journalism, to embrace the truly political power of pen. It is time to recognise how information can lead towards war, or steer us towards peace. Israel: a brief history and mythology

According to the Israeli historian, Ilan Pappé, the Israeli-Palestinian case clearly shows how historical disinformation and the manipulation of information can allow for the oppression of a population and legitimise a regime of violence and oppression. European mainstream media has often taken the narratives brought forth by Israel as objective, thus violating the moral right of the Palestinian people to their land. In his book “Ten Myths About Israel” (2017), Pappé aims to dispel these narratives through historical documentation. (1) Here a brief summary of some is presented, with an incorporated glossary, before attempting to make sense of recent events and their representation.

However this is only history: the heavy involvement of Europe and US in the Israeli-Palestinian case, as well as the complicity of international organisations and their failure to recognise the nature of Israeli violence persist today. Narratives have the power to create our world, and for this reason come with responsibilities. What happened last week Gaza has been under illegal Israeli military blockade since 2007. On Saturday morning, 7th October, the militant group Hamas attacked various Israeli areas surrounding the Gaza Strip, provoking one of the most severe attacks Israel has encountered for decades. Hamas is an Islamic fundamentalist military group, which over time had also gained popular support due to its provision of education, medicine and assistance to people who were suffering at the hands of Israel occupation in the Gaza Strip. This attack caused at least 200 deaths, while holding numerous Israeli civilians and soldiers hostages within the Gaza Strip. The Israeli response to this can be summarised in the announcement of a complete siege on Gaza by Yoav Gallant, Israel’s minister of defence: ‘’I have ordered a complete siege on Gaza. No electricity. No food. No fuel. No water. Everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we act accordingly.’’ Yet another narrative that validates the historical colonial and military project of Israel and its continued oppression of native people on the land. The violence that Hamas perpetrated against the Israeli state is not justified, but rather explained through this brief presentation of its historical and contextual origins. Along with this however, the violence that Israel has perpetrated against Palestinians for the last century MUST be explained. An omission of this is propaganda. The embracing of Hamas’s violent attack in the name of ‘’justice’’ is also falling prey to propaganda. But the recognition that Hamas is a fundamentalist and militarist group, as well as a symptom of the resistance to Israeli violence that stretches throughout history, can offer a more comprehensive way of framing of the problem, and hopefully shed light on its solutions. What is terrorism? According to a study conducted by the French site Le Grand Continent, the attack by Hamas divides the world in three groups: on the one side, countries such as in Europe, India and Kenya, that condemn the attack by Hamas and support Israel; a small minority that defends Hamas; and a great majority of countries that claims to be ‘neutral’ and supports a cautious de-escalation. In 1986, a young senator Joe Biden claimed that “were there not an Israel, the USA would have to invent an Israel to protect its interest in the region.” This was not only a political project, but “the best $3 billion investment we make”. The question here arises as to what Israel is a symbol of. Without looking back too far in time, the French president Emmanuel Macron wrote: “I strongly condemn the current terrorist attacks against Israel’’, while British Rishi Sunak reports his shock at the “attacks by Hamas terrorists against Israeli citizens” on the grounds that “Israel has an absolute right to defend itself.’’ If ''terrorist'' is understood as someone who advocates repression and violence, while disseminating terror for the achievement of their targets, then what makes the Israeli government less culpable than Hamas? The answer rests in narratives, propaganda, violence, silencing, manipulation and disinformation. The resistance and its victims To stand with the Palestinian resistance is not about legitimising the suffering of Israeli victims of violence who are most often civilians, young and old; but rather it means recognising the historical and ideological plays of power necessary to tackle the deeper problem that is occupation, imperialism and militarism. Resistance, particularly when this employs violent means for its survival, is often jeopardised by ethical contradictions: the suffering of one people, against another, for instance. However, in a military occupation, the play of power is not allowed to change without some form of it. To be violent against a system that oppresses and violates you is resistance, not terrorism. In the words of the Palestinian writer, activist and marxist internationalist, Ghassan Kanafani, “imperialism has laid its body over the world, the head in Eastern Asia, the heart in the Middle East, its arteries reaching Africa and Latin America. Wherever you strike it, you damage it, and you serve the world revolution.’’ The difference between terrorism and resistance is who is telling the tale, or rather who owns the most powerful means to make such a narrative come to life. The Palestinian cause is therefore not only a localised cause where the Palestinian people are expected to stand alone, but an opportunity for all those in the international community who wish to struggle against oppression and exploitation to stand in solidarity with the struggle of these people. Only in such a way, history will redeem itself from injustice and educate a future in which ‘’the oppressed will live, after their liberation by revolutionary violence, from the contradiction that captivated them.’’ Terrorism is an indication of power. More precisely, of who has the power to put forth such narratives of terror. To fight these, we must educate ourselves and find the root causes that lie at the feet of imperialism and militarism, as well as disinformation and propaganda. NOTES

ORIGINS.

According to the fideist current of fascist mysticism, faith and reason are incompatible: for such reason, faith trumps all else and establishes fascism as ‘’a religious concept of life’’, constituting a ‘’spiritual community’’ as defined by Benito Mussolini in 1932. Be it from a purely biological (Giovanni Preziosi) or idealistic-mythological point of view (Julius Evola), the fascist doctrine is founded upon the assumption of a hypothetical ‘’italic race’’, as a constituent part of the greater indo-european family. Niccolò Giani envisioned Europe as closed within a struggle between the Mediterranean world, close to the ancient Greek and Roman traditions that centered on the spirit (‘’Europe of the Aries’’), and the materialistic world born from the French revolution (‘’Europe of the Taurus’’). Whilst the latter was home to the ‘’semitic’’ theorists of both liberalism and communism, as in Russia, Great Britain and France, the former brought together Italy and Germany in ‘’this Europe of the aries that is arian, mediterranean and latin, and at the same time is Egyptian and Greek, fascist and nazist’’, in the very words of Giani. In other words, a conceptualisation that turned Italy in a war against the allies and in collaboration with the axis powers. Due to this ‘’historical continuum’’, sprouting from the Roman empire, the civilising force of Rome was reinstated through the idea of a pagan imperialism that was inherently racist and antisemitic. With this epistemic premise, Fascist mythology was to be accepted as a ‘’metareality’’. FASCISM AND THE STATE. ‘’The fascist mystic is faith and action, a dedication that is absolute but at the same time conscious’’: this is how Guido Pallotta described the nature of this school of thought. Profoundly rooted in faith, this proposed a vision of the world built upon Roman-catholic religion and a hierarchy represented by the traditional motto of ‘’God, Fatherland, Family’’, precisely in this order. The perfect fascist man had to be firstly a servant to god, then to his political leader (il Duce), then to his familiar sphere. According to these ‘’mystics’’, the New Man was one ‘’who does not want to be a twig at the mercy of cosmic laws, but rather a capable will’’, able to readily respond to adversities. He is one who is able to resist the scepticism, the materialism and the hedonism, that ‘’mortify the spirit of other contemporary peoples’’, in order to ensure the continuity of the fascist regime. The connections that deeply intertwine the fascist school with Roman-catholic religion are evident, in spite of their often-difficult relationship, as Pietro Misciattelli clams that the ethical ends of Fascism correspond to the ethical ends of the catholic church. Although objectionably a contributor to the fascist mystic school, Julius Evola himself wrote that nonetheless it was not possible to speak of a ‘’mystic’’ but rather an ‘’ethic of fascism’’: this movement did not respond to questions of higher values, of sacrality, which are essential components of any mysticism, but rather remained ‘’vague and conforming to the dominant religion’’. THE FASCIST GOVERNMENT. The one certainty that underlay fascist mysticism was that the sole source of the fascist doctrine was the thought of its leader: not only politically, but also spiritually, the Duce had the power to determine the truthfulness or falsity of his followers’ beliefs by his own will. As Giani stressed in his manifesto for the School of Fascist Mysticism, founded in 1930 and ceased in 1943, ‘’fascism has its 'mystical' aspect, as it postulates a complex of moral, social and political, categorical and dogmatic beliefs, accepted and not questioned by the masses and minorities. [...] A Fascist puts his belief in the infallible Duce Benito Mussolini, the fascist and creator of civilization; a Fascist denies that anything outside of the Duce has spiritual or putative antecedents.’’ Obedience thus becomes the demonstration of collective faith. In a polity where one has the power to determine the ideology of all, obedience becomes the coin for survival. In this sense, as reported by the Fascist National Party in the Dictionary of Politics, Vol. III (1940), ‘’fascist mysticism’’ becomes both the firm belief in the absolute truth of the Duce’s doctrine and the firm belief in its necessity for national strength. The mystique of fascism is defined therein as ‘’the most energetic and blazing preparation to action that tends to translate the ideal affirmations of Fascism into reality’’, thus the cult of one man through the study of his writings and speeches, accompanied by an absolute and faithful commitment to living in accordance with his word. Rather than contributing to the political sphere through constitutional means, under Fascism the sole expression of political dignity becomes the ability to make oneself a good servant to the government, to obey, ‘’to march in order not to rot!’’. Political action in this sense, however, was not the expression of one’s true being, outwith the space of necessity, as in the Aristotelian conception of philosopher Hannah Arendt: rather it is the will to conform, to assent, to surrender one’s political being to the shadow of authority. In his essential essay ‘’On the Duty of Civil Disobedience’’ (1849), Henry David Thoreau writes that ‘’disobedience is the true foundation of liberty’’. To challenge the laws or authorities that are in place in any political space must be a fundamental condition of any political system. In a political space, when the will of the authority is taken to be the law, then we assist to the mortification of civil rights and society. This is what Arendt calls the ‘’banality of evil’’: it is merely rooted in the inability to think for oneself in the face of authority. (Are we doing this because it is right, or because one is telling us to?) Yet evil has shallow roots, ‘’it can bever be radical, it can only be extreme, for it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension’’. Evil comes from the failure to think for oneself as separate from one’s appeals to authority, and a doctrine such as the fascist, constructed upon the cult of one man and the loyalty to his word, can in no way present a philosophical structure that survives any ethical or methodical scrutiny. The warfare, violence and militarisation taking place on our continent today, due to the Russo-Ukrainian war, all sprout from the same root. As in yesterday’s words of ANPI president Gianfranco Pagliarulo ‘’the peace that was granted in Europe for more than 70 years was the result of a long political, institutional and juridic journey, following the devastation of two world wars. We must immediately reclaim that vision and that project, result of the Resistance to nazi-fascism, and legacy of our resisters and our partisans.’’ To understand the viciousness and atrocity of fascism means also to understand how we, today, may change the turning of our times. To understand is our moral duty.

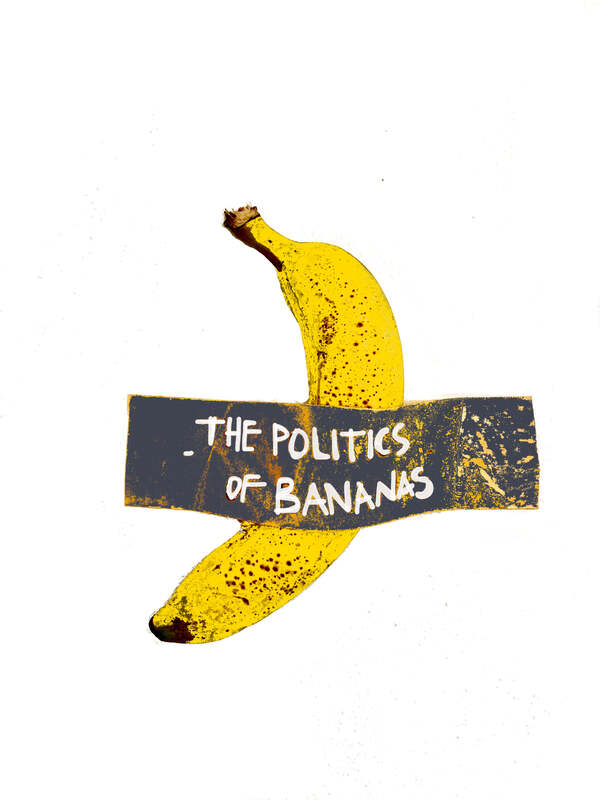

THE POLITICS OF MODERN SLAVERY The term ‘modern slavery’ has been utilised as a broad but controversial definition which incorporates many forms of exploitation of people. Since the Western abolition of slavery in the twentieth century, slavery has not vanished but has adapted and taken on different forms which have shaped our contemporary demographics and political-legislative realities. According to the researcher and community activist Gary Craig, slavery has changed to better accommodate an increasingly industrialised and globalised world where the migration of people to new contexts contributes to exacerbating their vulnerability to enslavement (Craig et al, 2019). Today, slaves can be defined as people who are held captive and coerced to work without compensation, and can be grouped in three main categories, as subdivided by the researcher and activist Siddharth Kara: bonded labour, trafficked slaves and forced- labour slaves (Kara, 2017). These include different sorts of phenomena, ranging from very modern practices to continuous historical ones such as debt bondage, serfdom, human trafficking, sex slaves, forced marriage or organ harvesting. Although abolished in name, slavery persists within modern society: an example of this, as the CEO of Anti-Slavery International claims, is 'the rate of British children trafficked in the UK [which] has more than doubled in a year.’ (Craig et al., 2019). The lack of awareness and the weak political discussion regarding these hidden chains, which are often overshadowed by the stature of history, have made all these individuals not only silent but also invisible. FORCED LABOUR AND THE ROLE OF BUSINESS With the proliferation of free trade, global value chains and multinational corporations, economic practices have extended to include ethical approaches (such as corporate responsibility or environmental standards) in business supply chains. Historically, the protection of human rights was the responsibility of the state; however, as businesses have gained more power outside of the control of international laws, they have been able to invest in practices that do not make them legally accountable nor require a moral commitment for the provision of responsible and transparent behaviours. This has led to appalling work conditions, wages and contracts for workers, which often include the exploitation of children or women in precarious occupations for salaries below the minimum wage, as well as unsustainable abuse of resources and environment (Craig et al, 2019). According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), forced labour is ‘all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily.’ In estimates by the ILO, at least 20.9 million people were victims of forced labour in 2012, 90% of which were subjected to individuals or enterprises in the private economy (ILO, 2012). Furthermore, profits per slave generally range from a few thousand to a few hundred thousand dollars a year, with total profits estimated to reach $150 billion (ILO, 2014). The market for forced labour surpasses all others both in supply and demand, promoting a low-cost manufacture to maximise profits and pressuring suppliers to provide the cheapest products (Banerjee, 2021). Today, most industries which dominate our Western world, from mining to textile industries to coffee and cocoa harvesting, are able to profit thanks to the exploitation of forced labourers. As consumers, it is our moral duty to be aware of the conditions and injustice involved in the production of foods such as chocolate, coffee and bananas, as some of the closest to our everyday lives. THE CASE OF BANANAS The banana industry presents itself as a clear case to explore how, politically and historically, one fruit can change the economic and ecological reality of many people. This case highlights how morality is deeply embedded in the food choices we make, which always affect and interact with a wider environment. The following analysis addresses some botanical and environmental factors which are structural to the cultivation of this plant and preliminary to its economic understanding before attending to the socio-political consequences for communities who cultivate bananas at a local level, as well as communities which import and consume these after their journey. Native to South-East Asia and brought to South America in the sixteenth century by Portuguese colonisers, bananas are fruits of the world’s largest herbs which come in approximately 1,000 different types (Rainforest Alliance, 2012). In the twentieth century, these are cultivated predominantly in Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Caribbean islands. The most prominent in export trade and the variety most commonly found in Western supermarkets is the Cavendish banana, which is the fruit of a long process of domestication which made it compatible to its environment and more resilient to the climate. Nonetheless, as banana production is based on genetically restricted and inflexible clones, this monoculture is particularly sensitive to pests, diseases, and ecological change (Perrier et al, 2011). For instance, the plant has remained vulnerable to the black sigatoka disease, which alone requires fifty aerial sprays and threatens the health of workers, soil and water. This cultivation also comes with the risks of unsustainable practices and the reduction of bananas’ agrobiodiversity as a species (van Niekerk, 2018). Although there have been some successful attempts in induced mutations and genetic modifications to make bananas more disease-resistant, these remain merely technological fixes: instead, we argue that what should be changed is our relationship with food and the food production system itself. The economy of bananas includes many countries in spite of its specific geographies. In fact, the EU and the US are the biggest importers of bananas, accounting for an annual average of 57% of global imports, as of 2017 (FAO, 2017). Bananas are also the second most sold product in UK supermarkets. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), only 15% of the total banana production is traded on the international market, while the rest is retained locally and constitutes a great part of people’s diets. Considering the fact that half a billion people rely on bananas for half of their daily calorie intake, particularly in countries such as Uganda and Cameroon, bananas contribute not only to food security, but also to substantial household income in many countries such as Ecuador or Costa Rica (FAO, 2017). Inevitably, the incredible demand for this product by supermarkets in the West has a great impact on the food sovereignty of many local communities. Food sovereignty is defined by Jaci van Niekerk (2018), in her research regarding the inauspicious development of a “new” transgenic fruit, as ‘the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems’. Our demands for products which have large environmental and social impact enables slavery’s assault on human dignity on an individual, but also communal dimension as entire communities become unable to provide the necessities for themselves and for this reason become dependent on external bodies. For this reason, it is crucial to frame this issue within local food and cultural systems, also recognising that malnutrition and hunger are not merely technical or biological issues but social problems originating from poverty, inequality, and an unfair distribution of resources. Ending hunger or promoting food sovereignty thus cannot be limited to a matter of gene transfers (van Niekerk, 2018), but must aim to address socio-economic and agroecological aspects first. These bio-technical approaches must be implemented and followed in parallel by socio-ecological considerations, such as land ethics or the empowerment of farmers and women, that reconnect them to the local dimension, otherwise they may risk undermining local food systems or traditional cultures. In a 2008 interview by Lesley Grant, the manager of banana growers’ association in St. Vincent and Grenadines speaks of the human cost of ‘cheap’ bananas produced in Latin America, compared with the better conditions of the small-scale, family-run Caribbean banana industry. In his words: All of this nonsense you hear of ‘cheap’ [bananas]. Someone has to pay upfront. They have to pay in blood or in terms of poverty. Because the person who comes and works for you for less than a US dollar a day, he is giving you his wealth. He is giving you the wealth of his children (Fridell, 2011). The cost of large-scale farming, as opposed to smaller productions, is stimulated by global demand and economic competition, thus a driver of strife and insecurity for many local families and communities. In fact, although Latin America and the Caribbean islands are the main producers of bananas, they present very different histories and models of production. In the Winward Islands of the Caribbean, for example, bananas provided one-third of all employment as well as half of their export earnings, before the World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules promoted global free-trade at the human cost of the islands’ small economy in 2005 (Myers, 2004). Through the dismantling of the EU-Caribbean agreement, where the EU removed non-tariff measures designed to enable this trade, communities were marginalised and the attempt to alleviate poverty and promote development though preferential treatments was abandoned by Western countries (Fridell, 2011). This became a problem from a Caribbean perspective, as the industry would not have been able to compete with the cheaper bananas of Latin America. The fair-trade movement therefore helped revitalise the banana industry in these smaller and more vulnerable countries in the face of the free market (Robbins, 2013). On the other hand, fair-trade companies dominate the market with very little commitment to ethical standards, such as the international company Chiquita, involved with the destruction of democratic movements in Latin America and perhaps also implicated in the overthrow of the democratically elected Guatemalan government in 1954 (Robbins, 2013). The case of bananas shows how the moral behaviours of markets can profoundly affect the biology as much as the social or environmental aspects of a place. THE FAIR TRADE MOVEMENT Fair trade appears to dominate the modern market in an effort of moral amelioration. However, the ethical foundations of this market approach have transformed throughout time to the point this is compatible with businesses’ logic of profit. Fair trade involves an attempt to combat inequalities and establish a network of solidarity, particularly between poor and rich countries, through ethical trade standards. In order to be officially considered fair-trade, goods must be produced by poor communities through cooperative democratic organisations and employ sustainable means for both workers and the environment (Fridell, 2007). Yet, as supported by Robbins (2013), it is currently questioned whether fair-trade certifications should be extended to multinationals or not. The dangers of doing so include the possibility of companies such as Starbucks or Nestlé, renowned for their very low standards, selling themselves as socially responsible bodies while in fact committing to very little (Robbins, 2013). The fair-trade movement was born in Latin America, to Liberation Theology priests and radical-liberal groups in Europe and the US. This was intended to represent a combination of Christian and liberal values directed towards labour, human rights and social justice (Lyon and Moberg, 2010). As presented in Gavin Fridell’s history of the fair-trade coffee market, this developed as an alternative network of trade organisations in the 1940s and 1950s. The fair-trade labelling system was consequently introduced in the 1980s, in the hopes of inducing bigger corporations to keep up with ‘ethical consumer’ markets in the West (Fridell, 2007). However, although producers of fair-trade coffee received higher wages than conventional producers, the difference was not enough to lift them out of poverty. This also came at the cost of increased labour, awareness of environmental impacts and a longer-term commitment for the workers, expected to carry a heavier burden of responsibilities (Robbins, 2013). The fair-trade movement today labels many common foods on the market. In spite of its moral foundations, to many this appears to be consistent with a neoliberal agenda, which defends the self-regulation of markets as the best way to promote social and environmental solutions as if they were commodities. In fact, according to Paige West (2012) in her analysis of New Guinea organic coffee production, fair-trade coffee is neoliberal coffee. This is because the farmer is seen as an object of empowerment whilst the consumer is the agent of such empowerment (Robbins, 2013). The exercise of responsibility is thus cast only on one side of the supply chain, prioritising the consumer’s moral comfort at the expense of the producer. By putting a price on fair wages, democratic means and sustainable practices, fair-trade certifications are merely commodifying morality. THE COMMODIFICATION OF MORALITY As consumers proceed through their meals, biting into another banana or sipping fair-trade coffees, many remain unaware of the slavery that is woven into the fabric of their daily lives, blinded by an economy of ignorance. What has been defined by Richard Robbins as the ‘commodification of morality’, echoing the words of both Fisher and Henrici (2013), represents a marketing strategy to increase the value and profit margin of final products at the end of their supply chain. Our commitments to fair trade should not aim to merely serve people’s consciences in this moral commodification, where they are able to buy their way out of the gap between morals and actions, but rather to provide a real positive impact, which today is clearly not fulfilled by fair-trade certifications. Returning to the ethics that underpin fair trade, which were originally rooted in Catholic social thought (Robbins, 2013), the correlation of consumption and communion is an important factor to consider as individuals have a moral obligation to think about their eating habits and shape practices in relation to their impact on others. According to the theologian and social ethicist Julie Hanlon Rubio, this could be interpreted in a theological perspective where consumers find themselves compelled to consider their personal role in global economic systems in which humans are exploited, and ensure that their actions are ‘not contributing to the maintenance of evil, when they could be contributing to the good’ (Rubio, 2016). The question of food justice must be interrogated on many levels: it departs from the preference, taste, or nutritional needs of any individual and approaches a communal dimension. Here, shared meals become a site of hospitality and solidarity, as well as ethical deliberation, creating strong foundations for these to interconnect with the global context. In this way, one’s personal and local choices are capable of shaping the lives of people on the other side of the world. In the twenty-first century, the role of educated consumers is thus crucial in the larger project of human liberation (Flores, 2018). A critical understanding of the places and commodity chains that our foods have to cross before coming to our plates is essential to empower and unchain individuals from their unawareness, as well as promoting a more positive relationship with producers and local communities. Through action, which should coherently accompany one’s moral choices, one is able to transform from a consumer to an agent of positive change. These considerations regarding our table ethics are crucial not merely “to eat our way to justice” (Flores, 2018), but rather to change the moral psychology of an economic order which is governed, in the words of Flores, by ‘the tragedy of consumer participation in the enslavement of others in the name of economic freedom’ (Flores, 2018). PROSPECTS After evaluating both the economic and moral implications of our consumption, particularly through the case of bananas, it is essential to realise that the (im)morality of actions contributes to many social issues and that food choices, more specifically, contribute to the maintenance of slavery. Solutions to modern slavery and market behaviours which enable the phenomenon must be found at multiple levels concomitantly, starting from the macropolitical and descending to the micropolitical. The reliance on moral solutions alone will not function if these are not also implemented at a macropolitical level, where the imperatives of profit maximisation and cost minimisation can fundamentally influence decision-making at a governmental level. The defence of social standards and welfare for both poorer and richer countries must be implemented with the same rigour, something that has not been applied to Western corporations who would otherwise not agree to participate in fair trade (Fridell, 2007). As Pogge (2005) claimed, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is ruled by a handful of developed countries implementing policies that profoundly impact poorer countries. He believes that the hypocrisy of these global institutions, who downplay the severity of hunger and rather commit to minor charitable assistance, is a direct cause of global poverty. Change must happen not to include poorer countries within the neoliberal development project, but to structurally change the way in which countries interact with each other across the global North-South divide, promoting an economy that is able to produce wellbeing for all rather than profit for few. This should also happen at a theoretical level, where more developed countries engage in research which could potentially benefit the poor (such as research on drought-resistant crops) rather than simply giving food aid in case of a natural disaster (Ouko, 2009). This approach can help some countries become more self-reliant, not merely relying on export as a fundamental source of income. At a macropolitical level, consumers must demand more accountability from the companies that produce their products in a way that goes beyond mere corporate social responsibility, through the introduction of third parties such as the judiciary. In this way, ethical discourse cannot be contradicted by corporate praxis, as happens with fair-trade certifications or ‘greenwashing’ advertisement where companies deceptively portray themselves as environmentally friendly for marketing purposes, and extreme biases and conflicts of interest can be avoided in an adequate way (Jones, 2019). Thus, ethical consumerism must not become a substitute for the civic action which is needed to create effective change through a change in governmental regulation at a national level. As well as this, it is crucial to note that the neglect of social relations of production is also followed by a failure to address unequal gender relations (Fridell, 2007). It is of utmost importance to note that the discrimination of women underlies every other form of discrimination. For this reason, the empowerment and protection of women’s rights must also be addressed as a fundamental issue in the food and agriculture supply chain. Therefore, civil society and intergovernmental organisations have a fundamental role to play in the greater political framework, demanding transparency and ensuring that political-economic institutions do not promote harm to farmers and producers in developing countries. Only through what Gavin Fridell defines as a ‘democratic political process’ (Fridell, 2007), producers and consumers can be given equal say and equal responsibility for decisions regarding the production and distribution of goods; something that is denied within the limitations of the global market. Ethical reflections must take into account that food is a basic human right which requires a combination of political decisions, technological solutions, social cooperation and individual actions to be ensured (Ouko, 2009). At an individual level, consumers must engage in informed practices, engaging with products that avoid moral commodification and advance positive impacts. As described by Benjamin Garner in his research on farmers’ markets (2015), these sites of direct farmer-customer relationships enable for community ties and social interactions to flourish in ways that are able to resist commodification. Through a sense of geographic embeddedness, consumers are able to reconnect to the natural environment and appreciate the specificities of their land through distinctive local products. As well as this, buying foods close to their sources promotes active engagement with the producers and consequently fosters a stronger sense of community, which is by nature ‘contingent and not commodifiable’ (Garner, 2015). Although the fair-trade movement originally attempted to construct such moral economy, moving away from the market to promote micro-interactions within and between communities, this has currently diverted towards the model of ‘isolated consumers’ (Fridell, 2007) due to neoliberal constraints. In an economic order driven by consumption, it will always be possible to purchase morality through ethical products: for this reason, it is crucial to cultivate alternative market models founded on mutual communication and collaborative human relationships, which are inherently non-commodifiable. In this way, local food systems such as farmers’ markets, local businesses and social enterprises become spaces of constructive economic interdependence between consumers and producers, on both an ethical and social dimension. The individual and global dimensions must be interlocked through the local: by promoting smaller systems of food production and trade, along with a community-based approach to food, the individual can develop an integral food ethic and the current global order of human domination and exploitation can be changed. To conclude, it is essential to recognise one’s role in the greater social and environmental picture. As consumers in the capitalist system, it is then of utmost importance that one’s practices promote local trade, direct relationships on the market and aim to avoid services which do not in fact reflect the social and environmental cost of production. It is crucial to remember that when one is not paying for this, someone else is (Fridell, 2011). Indeed, as modern slavery presents itself as the systematic denial of human agency, one’s ethical responses should aim to re-evaluate consumptive choices on an individual dimension, through reflection, understanding and responsibility, and promote new forms of interaction on a social dimension, through solidarity, mutuality and active democratic participation. It is the duty of all citizens who proclaim themselves against injustice and oppression to be aware of the hidden chains that still hold individuals hostage to the economy and question what small steps one can take towards an alternative market model that values people over consumption. Originally published by University of Glasgow's [X]position, Vol. 6, issue 2, 2021, available at: https://www.talkaboutx.net/xpositionvolume/6-2/Erin-Rizzato-Devlin/. REFERENCES Antislavery.org. 2018. UK lacks strategy to prevent child trafficking. [online] Available at: https://www.antislavery.org/uk-failure-trafficking-prevention/(Accessed 30/05/2021). Banerjee, B., 2021. Modern Slavery Is an Enabling Condition of Global Neoliberal Capitalism: Commentary on Modern Slavery in Business. Business & Society, No. 60, 2, pp. 415-419. Craig, G., Balch, A., Lewis, H. and Waite, L., 2019. The modern slavery agenda. Policy, politics and practice. Bristol: The Policy Press. Fao.org. 2017. EST: Banana facts. [online] Available at: http://www.fao.org/economic/est/est-commodities/bananas/bananafacts/en/#.YLbMXy2ZP_R (Accessed 17/06/2021). Flores, N., 2018. Beyond Consumptive Solidarity: An Aesthetic Response to Human Trafficking. Journal of Religious Ethics, No. 46, 2, pp. 360-377. Fridell, G., 2007. Fair trade coffee. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 3-100. Fridell, G., 2011. The Case against Cheap Bananas: Lessons from the EU-Caribbean Banana Agreement. Critical Sociology, No. 37, 3, pp. 285-307. Garner, B., 2015. Communication at Farmers’ Markets: Commodifying Relationships, Community and Morality. Journal of Creative Communications, 10, 2, pp.186-198. Ilo.org. 1930. Convention C029 - Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29). [online] Available at: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C029 (Accessed 17/06/2021). Ilo.org. 2012. ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour 2012: Results and Methodology. [online] Available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/publications/WCMS_182004/lang--en/index.htm (Accessed 17/06/2021).. Ilo.org. 2014. Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour (Forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking). [online] Available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/publications/profits-of-forced-labour-2014/lang--en/index.htm (Accessed 17/06/2021). Jones, E., 2019. Rethinking Greenwashing: Corporate Discourse, Unethical Practice, and the Unmet Potential of Ethical Consumerism. Sociological Perspectives, 62, 5, pp.728-754. Kara, S., 2009. Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery. Columbia University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gla/detail.action?docID=4588051 (Accessed 30/05/2021). Lyon, S., Moberg, M., 2010. Fair Trade and Social Justice. New York: New York University Press. Myers, G., 2004. Banana wars. London: Zed. Perrier, X., De Langhe, E., Donohue, M., Lentfer, C., Vrydaghs, L., Bakry, F., Carreel, F., Hippolyte, I., Horry, J., Jenny, C., Lebot, V., Risterucci, A., Tomekpe, K., Doutrelepont, H., Ball, T., Manwaring, J., de Maret, P. and Denham, T., 2011. Multidisciplinary perspectives on banana (Musa spp.) domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, No. 108, 28, pp. 11311-11318. Pogge, T., 2005. World Poverty and Human Rights. Ethics & International Affairs, 19, 1, pp.1-7. Rainforest Alliance. 2012. Species Profile: Banana. [online] Available at: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/species/banana (Accessed 19/06/2021). Robbins, R., 2013. Coffee, Fair Trade, and the Commodification of Morality. Reviews in Anthropology, No. 42, 4, pp. 243-263. Rubio, J. H., 2016. Hope for Common Ground: Mediating the Personal and the Political in a Divided Church. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. Ouko, J. O. , Thompson, P. B., 2009. The ethics of intensification. Dordrecht: Springer, Chapter 9, pp. 121-129. van Niekerk, J., Wynberg, R., 2018. Human Food Trial of a Transgenic Fruit. Ethics Dumping. SpringerBriefs in Research and Innovation Governance. Springer, Cham, pp. 91-98. West, P., 2012. From modern production to imagined primitive. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

A wave of dissent and protests has swept over the country to challenge the power of capital. As flags red with blood and wet with sweat have risen, workers of all trades have begun to leave their workplaces and organise in the face of rising living costs and the energy crisis, with an enthusiasm not seen in decades. Their strikes have proven the very fact that without the presence of working hands, labouring and toiling away, the functioning of society as a whole would not be possible. The workforce has the power to reinstate this claim each time it decides to withdraw its labour and disrupt the flow of social life: but what is the value of strike in a world that encourages competition over cooperation, harsh individualism over caring alliance, laxness over resistance? Is protest useful today, when algorithms govern and control our lives?

In Strike Strategy, the radical union organizer John Streuben defines the strike as ‘’an organized cessation from work. It is the collective halting of production or services in a plant, industry, or area for the purpose of obtaining concessions from employers. A strike is labour’s weapon to enforce labour’s demands” (1950). The first recorded strike action in history dates back to around 1170 BCE, when tomb workers’ in Deir el-Medina, Egypt refused to work due to a lack of wheat rations. Since then an immense number of workers have employed strikes as a strategy for achieving basic needs and rights denied by their hostile environment. The history of Scotland’s strikes goes back a long way, and is distinguished by its radical nature. In 1787, the first major industrial action of the county saw the Calton weavers as its first working class martyrs. Since then, a number of both national and imperial strikes led by coal miners, ship builders, engineers, transport and heavy industry workers and many others have spread and risen to this day. One of the most notable in the history of the Red Clydeside being the Battle of George Square, in 1919, causing 34,969,000 working days lost in the year before the workers returned to work with a guaranteed 47-hour week. As the ‘hot strike summer’ keeps getting hotter due to increasing industrial action, it seems that teachers, nurses, civil servants and firefighters may soon join the ranks as the cost of living crisis becomes incumbent. Conveniently, the government has stopped sharing strike data through the Office for National Statistics (ONS) website for the last three years. As mountains of waste begin to occupy the streets, the signs of changing times become all the more pressing. Under capitalism, the value of humanity is reduced to that of economic advantage, of money. Socially, hierarchies structure our relationships and perpetuate injustice as strata that sediment beneath layers of resentment and angst. James Connolly once wrote, in his 1915 The Re-Conquest of Ireland, that “the worker is the slave of capitalist society, the female is the slave of that slave”. Immorality on an individual scale breeds injustice on a social scale. By eradicating this from our very spirit, thus also striking from the industry of discrimination and exclusion, our choices can prefigure what our society ought to become. The worker movement towards fairness and equality and welfare, and against the supremacy of private property rights, must find its completion in the practices of the everyday, in the hope of liberating not only the direct slaves of the market economy but all of those subjected to its normalisation in the form of consumerism, individualism and commodification. We cannot commodify our political struggle in exchange for the petty comforts of convention and consumption: these come at the cost of our very rights, beings and liberties. Indeed, the strike is the sharpest tool workers have to fight against the logic of profit and for a future that is more fair, collective and solidary. Freedom shall come only when, in the words of James Connolly, the people will own ‘’everything from the plough to the stars.’’ Ye wouldnae hae your telly the noo, if it wasnae for the union! The question concerning technology does not merely concern human artefacts, but it is also a question of ethos, of reverence, of gratitude. We forget to hold our phones as miraculous shrines that incapsulate sound from one side of the globe and transfer it to the other; to fly across countries realising we are merely mimicking the flight and composition of birds; to turn the lights on reminiscing the struggles of fumbling in the heart of the night, whilst the aid of sunlight is brought to life on command. Thanks to human brilliance, life is made easy by artifice. It is made easy, but not simple. Through technology, we have accommodated our needs and dangerously transformed them into necessity. The attitude of humanity remains stolid in the face of the wonders it has created. In the words of Hannah Arendt, ‘’the more highly developed a civilisation […], the more it will resent everything it has not produced’’ (1951). Everything that humankind has not produced or created, but merely received as an element of its environment has increasingly become stigmatised within the contemporary construction of our reality, where technic has come to prevail as an absolute language. By distancing ourselves from our given environments, we have come to despise those things that are outwith human control, irreducible to technical solutions. This moment in time can be seen as a crisis of reality, where the lack of imaginative and creative power leads us to a view of our world that is sterile, disintegrating, unchangeable. We should never forget, on the other hand, that it is always in our power to reimagine and thus recreate alternative reality systems: renewing our cosmologies can radically give birth to new ways of conceiving of our individual existences, as well as organising our socio-political lives.

It is true that throughout our existence, we take place: we cross sites, navigate geographies, belong to expansions by ‘’taking place’’. Thus, by contributing, changing, affecting our environments. Every action, no matter how small, has an impact that never truly transcends its space: even a prayer for instance, remains rooted in the territory of its utterance or contemplation, which in turn becomes a sacred space. We make place, as we take it. The dangers of technology are that it gives us the illusion of transcendence, where space becomes meaningless as we create a global network of scientific, political, technological, administrative that are thought to address the environmental catastrophe we have created, as well as aid our survival in the world. However, we have yet to learn that a dynamic ‘system’ such as nature cannot be managed as if it were a machinery system: by translating all we know to the language of science and technology, we overlook the very needs of our biosphere. We must remember that nature, society and machines require different languages. From here, the distinction between ‘complexity’ and ‘complication’. In the words of Kvaløy Setreng (2000), ‘complexity’ is the ‘’dynamic, irreversible, non-centrally steered, goal-directed, conflict-fertilised manifoldness of nature and the human mind/body entity’’. On the contrary, ‘complication’ is the ‘’static, reversible, externally and unicentrally steered, standardised structure-intricacy of the machine’’. Whilst complexity is merely a property of the natural world, where ecosystems are intertwined and co-dependent, different species and languages survive amongst each other, complication is the man-made construction of a reality where the standardisation of scientific and technological language is applied to all things. We expect to treat the brain as though it were a computer. We wish to solve homelessness by applying spikes to park benches. We cure depression with chemicals, rather than looking to the greater environment of reasons and causes within which this happens. If we limit ourselves to the complications we create, rather than recognising and accepting the potentially enriching complexity of our world, then we will constantly live in a world of edges and obduracy where technological-fixes become the only way of solving our problems, yet creating more on the long run. Although we are systematically taught to accept the age of technologisation and computerisation as something intrinsically positive, we must not forget to balance its scientific and developmental advantages to its social, political, ecological risks. The way we ease a complicated world can shine light on the way we overlook the possibilities of the reality that surrounds us, helping us consider the political and social consequences of such devices and ‘augment’ our reality without resorting to digital means. To be easy is not to be simple: sometimes the small rituals of cutting wood or lighting a fire to keep warm and cook food can help us feel awe at the magic of a mobile phone that can reach the opposite side of the globe. Our brains are not machines, and as such it remains in their deepest power to break through the language of our times and touch the flesh of another world.

In the last few days, we have been bombarded with photos of destroyed buildings looking onto the streets of Kyiv; footage of young Palestinian girls being violently attacked by the Israeli police force; stories of massacre and suffering as the future of an Ethiopian political community perishes; accounts of people with no home, people preparing to wage war, people waving their uncertain farewells as half their families have to rush onto a train leaving their men and streets behind. Hands waving, eyes tearing, hearts pounding in the face of the immediate imposition of the future, opening as a wound in their existence. People are the victims of war, not nations or ethnicities or religions. There is no segregation when it comes to such violence, no differentiation between cultures, no dissociation in terms of feelings. Amongst all the visions that have occurred to me in the last few days, one has remained with me particularly: a vision of ‘peace’, written in a Nigerian dead language on the breast of a friend. Perhaps the symbols of a dead language can keep us from despair, more than those prolific spiels of words that attempt to accuse, defend, justify what is happening around us in the public space. There is nothing but an exercise of humanity to be made to save us from capitulating into the pits of brutality.

For this reason, instead of providing the politics, the deliberations, the intentions of violence that have occupied the pulpits of government in the last weeks, however useful this study may be for understanding the reasons of many such occurrences, these present words are an emotional response to the circumstances. To attempt to legitimise the facts through their mere political explanation, is to legitimise the very logic of warfare. In this, I believe there is no logic. There is no sanity, no empathy; there is not love for one’s nation nor one’s people. There is strategy or tactic conducted in the name of power. The study of ‘warfare’ and ‘security’ can risk romanticising the issue or alienating people from the emotions of those who are affected by their consequences. It is good to be reminded, that the fact we are not currently surrounded by the blasting screams of warfare is a pure matter of luck. It could be us, our family, our homes torn to pieces by the decisions of men sitting around a table from their thrones of egoism. War merely redefines spaces, powers, dialectics. The cost of this, however, is humanity, both physical and spiritual. There is no other prayer one should undergo in these times but the relentless commitment to kill the seeds of hatred and violence that may inevitably arise within us, and to defeat them by desperately searching for ways to communicate and compromise with the other. It is from this very choice that our survival may depend. In such disheartening situations, it is important not to despair, and to remember that this is not the first nor last, nor only war that is tearing people and lands apart. As warfare is nothing but a performance of humanity at its worse, it seems appropriate to solely mention one of the greatest play writers of the last century. Thus, in the words of Bertolt Brecht, we must remember that in each war there will be losers and victors: amongst the losers, those who will suffer from hunger will always be the poor people; amongst the winners, those who will suffer will be the poor people. By realising that war is not a matter of power over an invisible ‘Other’, but an attitude towards how we treat human beings as a whole, we will be careful not to ‘’sit on the wrong side because all the other seats were taken".

Each place has a voice. No matter where we find ourselves, the search for the sacred has belonged to human culture since the beginning of time. Along with this search, the building of sacred places has been an essential part of the pursuit of religion. The rising of these physical idols, these dwellings of the divine, are what the ancient Greeks used to call ‘temenos’, meaning a piece of land dedicated to a god or sanctuary. Within this holy precinct, the land is allowed to sing, voicing its quiet hymns to reclaim the air itself. This momentum, defined by space rather than time, is what allow humans to enter into contact with a reality greater than themselves. In fact, it should not be regarded as a breach in the veil of reality but rather as a transversal distention that coincides with the land itself, that follows its gentle swellings and its grieved recesses. In the Western world, we have reached an age where religion, according to some, has been relocated. In this sense, ‘religion’ has not been lost: it has just changed its form to reach a state in which we do not recognise it as such anymore. The human search for sacredness, however, makes it impossible to abandon the need to transcend one’s self and rip open the burning hole at the heart of the ego.